Bruce Baillie visits the Bay. We have a screening in his honor.

Please join us on the evening of Friday, September 23rd at New Nothing Cinema for the next installment in our Salon series. This month, we’re pleased to welcome legendary filmmaker Bruce Baillie, founder of Canyon Cinema and San Francisco Cinematheque. There will be a brief reception prior to Bruce, Dominc Angerame and Linda Scobie’s introduction of his films. As always, the screening will be followed by conversation.

The Canyon Cinema Salon Series is a FREE event hosted at New Nothing Cinema (located at 16 Sherman St, off Folsom between 6th and 7th in SOMA).

7:00pm- Reception

7:30pm* – Screening and discussion.

*Note: Street entrance locked at 7:30 – please arrive on time.

The program to include:

Mr Hayashi (1961)

On Sundays (1961)

Roslyn Romance (Is It Really True?) (1974)

+ much more!

This is one of three events honoring Bruce Baillie on his visit to San Francisco celebrating his 85th Birthday. The festivities are co-presented by San Francisco Cinematheque and Canyon Cinema, in partnership with Dominic Angerame and Linda Scobie, and supported by the generosity of the George Lucas Family Foundation and The Owsley Brown III Philanthropic Foundation. A very special thank you to Rock Ross from New Nothing for his hospitality.

Refreshments for this event are provided by Ordinaire Wine – purveyors of fine natural wines.

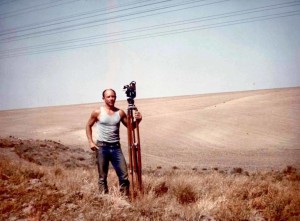

Born in South Dakota in 1931, Bruce Baillie served in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War and studied filmmaking for a year at the London School of Film Technique. He moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1950s and within a few years became a guiding light of the New American Cinema. Simultaneous to his earliest personal experiments in 16mm, Baillie launched Canyon Cinema in the redwoods over Oakland in 1961. As he recounted to interviewer Scott MacDonald, “Immediately I realized that making films and showing films must go hand in hand, so I got a job at Safeway, took out a loan and bought a projector.”

As Canyon fanned out across the Bay Area and developed into the cornerstone experimental film distribution cooperative it remains today, Baillie took to the road to collect material for a series of intensely lyrical works that helped to define the look “visionary film” in the 1960s. Early efforts like On Sundays and The Gymnasts gave an inkling of Baillie’s prevalent mix of documentary and fantasy, as well as his penchant for ripening superimpositions and exploration narratives. Canyon newsreels such as Mr. Hayashi (1963) proposed a concentrated form of cinema-as-haiku that Baillie would return to in later works like ALL My Life (1966) and Pieta (1998).

Baillie’s fully realized quest films (Mass For The Dakota Sioux (1964), Quixote (1965) and Quick Billy (1970) in particular) envelope laments for humankind’s destructive impulses in luminous formal surfaces. As much as his contemporary Stan Brakhage, Baillie developed a bold film language to convey visual phenomena outside the realm of dramatic realism. Baillie’s artisanal mastery of cinematographic layering, in particular, brings about immanent perceptions of the radiance and transience of all things. The lucidity of vision in his work is an end in itself, betraying an almost amorous desire for spiritual ballast.

In a simple ballad like Valentin De Las Sierras (1968), for instance, the intensity of proximate vision evokes a radical empathy with other beings. In Castro Street (1966), perhaps his most famous work, an industrial thoroughfare supplies Baillie’s Bolex camera with the raw materials for a matted tour de force of synaesthetic effects. Film scholar P. Adams Sitney wrote that Baillie’s “problematic study of the heroic” and “equivocal relationship to technology” served to complicate his resplendent lyrical forms, though one could just as easily say that the films he made during this period give poetic expression to the inner struggles of the 1960s. His epic Quick Billy grew out of a brush with mortality while living at a commune in Fort Bragg, California, and its expansive passages through interior illuminations, autobiographical reflections and Western pageantry make it a fitting capstone to a turbulent decade.

Baillie continued to make films into the 1970s and ’80s, eventually switching to video for works such as The P-38 Pilot (1990). Among other honors, Castro Street was selected for preservation in the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 1992. He is currently at work on Memoirs of an Angel at his home on Camano Island. – Max Goldberg