Interview with Canyon Cinema founder Lawrence Jordan

Posted September 14th, 2010 in Announcements, News / Events

Lawrence Jordan, a personal filmmaker, fine artist, and educator, at home in Petaluma. photo: CineSource

Jordan’s Animated Journeys

By Doniphan Blair

A titan of personal film, Lawrence Jordan went to high school with Brakhage, formed Canyon Cinema with Baillie, and created masterful 16mm films – and even his own genre

Lawrence Jordan creates handcrafted cinema, notably his dreamy animated pieces made from collages of old engravings. They suggest what a poet might have made had Edison invented film in the Romantic era. Take his 1957 short “Spectre Mystagogic:” How’s that for a Romantic title? But Jordan’s films are hardly spaced out. Indeed, they are quite precise, technically as well as aesthetically. To provide a richer feel, Jordan animates at one frame per move, as opposed to two or three, despite the doubled work load.

He has also made live action films, narrative features, personal documentaries, and pieces of no discernible genre save that of “Jordan.” When I visited him recently – he looks great at 76 – he said “What saves me is that I like a lot of different things. A lot filmmakers get stuck on the type of films they make and [think] everything else is crap. I didn’t get into that.”

Another thing that saves him: In addition to being utterly artistic and technically adept, he’s mellow and open-hearted. Hence, he was a great teacher, my favorite at film school. In 1974, I was an over-ambitious San Francisco Art Institute student trying to shoot a feature called “Sammy Delirium.” Lawrence would calmly and deliberately dissect my scenes, neither adding a fear of the immensity of the project nor subtracting the need for rigor.

“Personal film” is his preferred term for what is variously labeled avant-garde, underground, alternative, art, abstract, poetic or non-narrative. Unfortunately, no term quite hits the art from on the head, often prompting Jordan to explain, “I work with film the way an artist works with canvas,” or “The only relation [my work] has to ‘big films’ is the stuff that runs through the projector.”

Jordan launched his journey in high school in Denver, which he attended with another personal film master, Stan Brakhage, although they only studied and watched films and didn’t make any together until after graduation. Since moving to the Bay Area in 1955, Jordan has immersed himself in the region’s art, poetry and mystical inner workings, as well as film scene, helping found the Canyon Cinema Cooperative, among other things. He has created over 40 personal films and “poetic documentaries,” as he likes to call them, and three dramatic features, although he is most known for his animated collages.

In 1970, he received a Guggenheim Award to make ‘The Sacred Art of Tibet,’ a personal doc, and became chair the Art Institute’s film department. A few years later, Cannes invited him, along with other West Coast film artists, and he has shown and lectured throughout North America and Europe. Indeed, the Toronto International Film Festival just called: they want to show ‘Cosmic Alchemy’ and ‘Beyond Enchantment,’ his two most recent films – not because he passed the submission review but because the programmers wanted him.

I visited Lawrence in his lovely Petaluma home, which faces out on a field (a deer wandered by as I left). It faces in on a lush garden where he has a small but amazingly well-outfitted and complete film and fine art studio. We started by reminiscing about meeting as teacher and student.

CineSource: I thought the Art Institute was beautiful, and it was especially beautiful in the ’70s.

Larry Jordan: The ’70s was the high point. Then the graduate program ended. A lot of those people are still around. Some of my students are teaching me digital now. Some are in charge of companies: David Weissman at Video Arts, John Carlson at Monaco.

The ’70s was the height of not only the Art Institute, but of San Francisco [art] filmmaking. That was when James Broughton and many people were making poetic films –

And Gunvor Nelson.

And George Kuchar, and Al Wong.

Then Ernie Gehr came out. My hirings at the Art Institute were Gunvor Nelson and George Kuchar.

And Walter Murch.

Yes, but I didn’t meet him. I hired him over the phone for a semester when I went on sabbatical. James Broughton was doing a few classes before I started, but wasn’t in the film department. We started getting more active and he came in. We had a pretty strong group at that time, as you remember.

Yeah, and it was also strong with students. It was the two together, really.

The students really wanted to make film. Of course, everybody at that time wanted to make film.

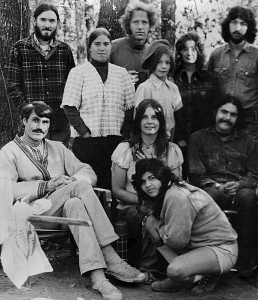

Film Camp Flashback, Circa 1974 On location in Laytonville, N. California, for Jordan’s 16mm feature ‘The Apparition,’ which he wrote, directed, produced, and shot. (Top, left-right) John Cavalla (taught sound at Art Institute), Jordan’s daughter Lorna Star (now lives on a ranch in Idaho), Robert Krigel (actor), Steven (the kid), Diane Levine (went to LA and became an extremely high-powered and wealthy television producer), a man we couldn’t identify (sorry); (Second row) Jordan, Paula Mulligan (actress who narrated two of Jordan’s films), Larry Houston (of the bushy mustache, also SFAI student), and kneeling, the ‘craft service’ chef (whose name is forgotten but whose food is remembered – delicious!) photo courtesy L. Jordan

There was a diversity of opinion. In the ’80s, [SFAI] became very polarized with Marxists and Structuralists. You know, the culture wars. Once, it was me and James [Broughton] against the class. They were decrying ‘rich art,’ saying that some film we saw was indulgent, not ‘of the people.’

Okay, let’s stay on that one. Art is elitist because all this political stuff is not high art. It’s propaganda. So what you have is people making art for art’s sake. It’s elitist. Let’s don’t avoid it. It is. When Adam Sitney [a historian of avant-garde cinema] came to lecture at the Art Institute, someone said, ‘These films are very self-indulgent.’ That is the definition of American avant-garde film. Indulgence in self, let’s don’t avoid it. It’s people exploring themselves.

That’s what my work is about. My interface with the inner world is animation – that’s my inner world. My interface with the outer world is my personal poetic documentary, as I call it. I taught a class called ‘Personal Poetic Documentary.’ It goes back quite a ways: New York in the ’50s, the work of Helen Levitt [the photographer] on the street. It’s a tradition where the artist goes out with a camera and interfaces with the real world. Or the camera turns inward and you’re exploring your unconscious. So yes, the films are self-indulgent because they indulge in the self.

When Broughton and I were arguing against the Marxists – the irony was the Soviets invented a lot of the avant-garde techniques.

Oh yes, the Soviet cinema is so rich.

Did you run into the Marxists in the ’80s?

I never did. Was that coming from the students?

Yeah. In the ’70s, it was all very congenial: there was a Moroccan filmmaker, Simone Edery, a guy making a surf film, another we helped shoot 360 frames per second – he was slowing down explosions. But then I went to South America for two years, and, when I came back, it was odd, it had become very cliquey. At first, I thought, ‘These students, I don’t know, I just don’t like them.’ But then I read somewhere that art students are intensely neurotic because they aren’t even artists – they’re just art students looking for their identity. So I forgave them. I stuck around ’til ’91 and enjoyed the hell out of it, even with the students.

I had a different experience. The conflict that I ran into at the Art Institute was in the faculty. Not in the ’70s – there was no conflict then – but later. I don’t know if it was the type of classes I was doing or whether I was intimidating or something. I taught for 30 years at the Art Institute. I taught introverted geniuses who never gave me any trouble. It was an ideal job. You could never ask for anything better.

I was one, I suppose, and enjoyed it immensely.

I always felt that when we got the class going, it was just about film – we didn’t get into theory or criticism. We just looked at film and made film and enjoyed it. In the class, everything ran smoothly. The school had its problems, but always in the faculty.

Do you want to define that? Not to incriminate, just the philosophical fault lines?

No. I’m not going to get into that because that is over.

An Image From “Sophie’s Place” (1986) uses an archetypal figure that appears in other Jordan films. ‘I do not know the meaning of any symbol or character. As soon as I attach some meaning, the sequence falls apart. The meaning is entirely at the disposal of the viewer – like a Rorschach Test. I am trying to interact with the unconscious of the viewer; that is main philosophical thing I work from.’ photo courtesy L. Jordan

You helped start Canyon Cinema, right? I just spoke with the Canyon Cinema’s director Dominic Angerame [see article]. It was you, Bruce Baillie, and Robert Nelson?

Bruce started the showing part in Canyon [a hamlet in the Oakland Hills]. Robert Nelson, Van Meter, and I started the co-op [aspect] because we needed a place to distribute our films.

So you were the guys running it, shipping films?

We wanted to get out of sending films from home. We wanted to hire somebody to send them out. At first, it was in somebody’s home. Then, I remember Robert Nelson and I building walls in the basement of the Intersection Church so Edith Kramer could have an office. Edith ran Canyon for a number of years and went on to the Museum [of Modern Art] and finally ran PFA [Pacific Film Archive].

We started the co-op, modeled on the New York [Film-makers] Co-op. But Canyon became a much better co-op, eventually. Dominic and his partner decided at some point that they would get really business-like, and they did. They really got customers and made it viable. I still talk to Dominic about once a week.

When did you join that community? And where did you come from?

I grew up in Denver. Stan Brakhage [one of the best know avant-garde filmmakers] and I went to high school together. Both of us came to San Francisco in the ’50s. I spent one summer in New York, but then came back. From 1954 on, I have been in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Those were pretty intense days: the early ’60s through the ’70s. There was a lot of freedom and new things getting started. In the ’50s, it was just so boring, socially. What really kicked off the whole ’60s revolution were the Joseph McCarthy [‘Red Scare’ Senate Committee] hearings. We were all huddled around the radio listening to that. And from that time on, we wanted to break away from that kind of society.

So McCarthy started the rebellion inadvertently?!?!

Yeah.

You made films in high school with Brakhage?

No, we did some after high school, at his house in Denver, and a couple here. One was called ‘Unglassed Windows.’ I started making films in college – that was 1952 – at Harvard. There were no classes, only a film club. The seniors taught the freshman.

That sort of club filmmaking has been going on for a long time, right?

In the late ’50s, Bruce Conner and I started a film society because there was nothing doing in San Francisco. I shouldn’t say nothing: Jordan Bellson would have showings occasionally. He did Vortex, of course [electronic music/film projection performances at the SF Planetarium] and there were some filmmakers, Hy Hersh, Pat Marx, who did sporadic, personal showings.

Bruce Conner and I got into a church on Washington Street and started a thing called Camera Obscura. After that, I built a theater on Kearny, just off Broadway, called The Movie, to show experimental films. Before it opened, I sold my interest to a partner. I could see that I could not make films and run a theater at the same time.

What sort of films were they showing? ‘Andalusian Dog,’ Maya Derren?

Those sorts of things. There was a couple named Rainey, who ran it as a combination of foreign film and experimental film. Kenneth Anger lived above the theater. There were two apartments. When I was working there, I lived in one. Eventually that became a porn film theater; I think it still is.

Kenneth Anger, was he local?

No, mostly from Los Angeles. Well, he moved around, he was in France, in Europe, a lot.

What was the groundbreaking film that put underground film on the map? Was it [Anger’s] ‘Scorpio Rising’?

Well, that really made the rounds. There were a lot of blockbusters. Later, ‘Wavelength,’ by Michael Snow. Kenneth Anger and Maya Darren were the films that Stan and I looked at in high school and got us excited about film.

How did you find and get those films?

There was something called Cine 16 run by Amos Vogul in New York [the Austrian-Jewish refugee who founded the New York Film Festival]. We were also renting films like ‘Intolerance’ and ‘Birth of a Nation’ from the Museum of Modern Art [NY] rental library.

What films got you really excited around that time?

I especially liked Anger’s ‘Eaux D’Artifice’ [1953], filmed at Tivoli Fountains in Italy, where all the décor is very Baroque. That was a very successful combination of film and music. That influenced me a lot.

But it wasn’t until I moved to Marin County that I had an epiphany one day. I was very taken with the collage novels of Max Ernst. At that time, they were not on the market – you couldn’t buy them. So Jess lent me his copies – Jess and Robert Duncan were my mentors [Jess Collins, was a SF painter and collage artist, who died in 2004 and went by one name; Duncan, 1919-88, a poet, and devotee of Western mysticism, was from Oakland].

I photographed each page with a 35mm camera and was developing them one after another in the dark room. One day, I took a nap and woke up with the thought: I could make those [collages] move. I started buying books of engravings. I was lucky with that first film, ‘Duo Concertantes’ [1964]. There was a whole chain of experimental festivals at that time.

They just up and started at that point?

Yeah. [‘Duo Concertantes’] was winning prizes in these festivals even before it had a soundtrack. Then I was improvising with the radio for sound while I was showing the film in a café in San Francisco, and on came this sonata. It played with the film from beginning to end. I called the station, found out what it was and that became the soundtrack. I found out later that Kenneth Anger had done some of that. You pluck it out of the air. That stuck with me all these years. The sound for films just comes … when it’s time. Sometimes, you don’t even know where it comes from.

Interesting. Now that was your first film collage film. Are there a couple of other titles that you feel are strong pieces? I know you also did narratives.

Yeah, but the narrative films came later, in the mid-’70s. I did one I think that is pretty good. It is called ‘The Old House Passing.’

I think I saw that one.

I’m sure you did. I think that was the most successful. I did a long fairy-tale film called ‘Hildur and The Magician,’ and then kind of a supernatural film called ‘The Apparition,’ in color, when we were first getting color negative in 16mm. Those don’t show very much. The animation is what everyone wants to see.

Have you ever shot a film in digital?

No, just family films for fun. Film always has one advantage. It slows you down. You can’t make it in such a facile way as you can with digital equipment. Making digital films is not cheap. It costs nothing to actually shoot, but the equipment to make a good digital film costs a fortune. So you’ve either got to buy expensive stuff or you’ve got to pay expensive rental in postproduction.

You can edit so easily in digital. But film slows you down and that’s an advantage. [Steven]Spielberg said, fairly recently, that he cuts film, not digital, because film gives him time to think between cuts. That’s going to work to the advantage of young filmmakers. Digital cameras are going to spawn – I don’t want to be judgmental here – stuff that’s made quickly.

Ashley [James, Oakland docmaker and KTOP director, see article] says he runs into people shooting digital who know nothing about lighting, nothing about composition. They think all you do is press a button. But Ashley, when he comes here to shoot, will spend two hours just getting the lighting set-up. [James was shooting ‘Moments of Illumination,’ a movie about Jordan, directed by his wife, Kathryn Golden, both of students at the Art Institute in the 1970s.] Of course, Ashley’s takes are longer and that gives Kathryn a lot more material to work with when she edits.

That’s the advantage of digital: You get a lot more material and you can get to it quickly. With some filmmakers – not all – that will again make things too facile. Everything will look kind of the same. That’s what happens with commercial film. That’s why the number of bad commercial films is astronomical.

So you never tried making a piece digitally?

I shot a little for Joanna [Jordan’s girlfriend] some years ago on videotape, but it just doesn’t turn me on. The thing is: with a film camera, you have a very limited amount of film in the camera. And that film is very expensive. So what it does for me is, it ratchets my brain up to a different level. I am really working at my highest possible level when I shoot film. This is the real thing; it’s very expensive; I don’t have much of it. So, I’m gonna get a really good image or I’m not gonna turn the camera on. That slows you down.

And then the editing, I love handling film. I like pushing buttons on sound, but not for having images pop up. I like having pieces of material. It’s like making collages. I actually like gluing one piece of film to another. I like splicing one piece of film to another and seeing what it looks like. Making one piece at a time.

Do you edit on a flatbed?

I’ve got a good – a really good – KEM. I think with digital you have a whole lot of material so it’s like a sculptor with a huge block of stone. And you chip away at it and take away what you don’t want. But with film, at least with me, it’s like building up one piece of clay on another piece of clay; it’s putting things together rather than chipping away. Have you seen my four-disc DVD album?

No, I’ve heard about it though.

It was beautifully done. It has most of the good stuff, except the long narratives. Look how nicely done the DVD is. It’s by Facets Mobile Media, which has distributed my work for years [Jordan also distros with Canyon, which doesn’t do exclusives].

I did a two-hour film while Joanna and I traveled. This is part of the H.D. trilogy film, with a long poem by the poet H.D. [Hilda Doolittle, a friend of Ezra Pound, and teacher of Duncan]. The film is about a woman traveling by herself and coming to terms with aging. Joanna plays the central role. So it’s a travelogue and [evokes] a poetic theme.

Okay, [my films] I like a lot: ‘Our Lady in the Sphere,’ [1969], that rents the most. ”Orb,’ [1973], ‘Once Upon A Time’ [1974], ‘Moonlight Sonata’ [1979], ‘Masquerade’ [1981]. Then I did a long animation, ‘Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner’ [1977, 45 min. Jordan uses 24 animation moves per second, rather than 12 or 8, saying, “It gives a different feel.’]

Also with cut-outs?

Yeah, Doré illustrations. And then I did a feature animation called ‘Sophie’s Place’ [1986], 86 minutes. ‘Visible Compendium’ [1991], and ‘Blue Skies Beyond the Looking Glass [2006]. Then one disc of the live films. There was also ‘The Sacred Art of Tibet’ [1972].

A documentary?

Yeah. And I did a documentary on the work of Joseph Cornell. I was his assistant in 1965 back in Flushing, New York. I learned box making [which Jordan continues to do. His gallery work, ironically, is more lucrative than his films].

That was the period you were in New York?

No, I went back especially for that. ‘Visions of a City’ was shown a lot, which is a film I made in the ’50s with Joanna’s ex-husband, Michael McClure, the poet.

Would that be your oldest film that shows?

Well, it’s one of the earliest films on here. ‘Waterlight’ is on the album and it’s the earliest. That was 1957. ‘Visions of the City’ started in 1957, and then I re-edited it in 1979.

Revisting a piece, kind of a rarity, no?

There were a number of things I reworked after I came back from Europe the first time. I just had the energy to finish things that were on the shelf. I was never able to cut the footage I shot of Cornell in 1965 until that ’79 period.

Too close to it?

Yeah. I knew I’d mess it up. ‘Winter Light’ is a film I like very much. I made that in 1983 three years after I moved here to Petaluma. It’s a portrait of Sonoma County in the winter, when there’s lots of fog. Then there’s ‘Postcard from San Miguel’ [1996]. We used to go down to San Miguel in Mexico and we did a film there.

Were most of these films shot on a Bolex?

All the early film, from the ’50s and ’60s, was with a Bell & Howell [with a wind-up crank]. ‘Our Lady of the Sphere’ and ‘Hildur and The Magician,’ I shot both of those in 1969. About 1968, I got the Bolex. And everything after that – pretty much – was shot on the Bolex, except the H.D. trilogy film. While I was traveling, I liked the older camera, the Bell & Howell. It’s not an expensive camera and it’s very durable. It’s a good handheld camera.

For synch sound, you’d rent an Eclair or something?

For ‘The Apparition’ [1976] we used a school camera [SFAI’s Éclair]. That’s the only one I did with synch sound.

Really? Even the documentaries were voice-overs?

Yeah, because most of the documentaries are short and very personal. The sound is manufactured and people don’t talk [on screen].

What are the trends you’ve seen in art filming in [the last] 40 years?

The audience is always falling out of love with the personal film and getting into topical film and issue film and sociological film and political film.

Like by Michael Moore?

Yes, and ethnic film. But for the person who is making film in the same way that the painter is painting on canvas, in a purely personal way, that’s a difficult road.

I’ve always been blessed with good audiences. The people who show up seem to know what they’re there for. We have a pretty good time. The only time I ran into an ideological dust-up was in the ’70s in New York at the Millennium [Film Work Shop, East 4th St]. I was showing ‘The Sacred Art of Tibet’ and half the audience thought it was a wonderful film. The other half thought it was horrible: a Westerner was saying something about these [sacred] images. I didn’t say much. The audience argued back and forth.

You had hit gold.

It was fine.

Art film does keep going out of favor, like jazz, but then it comes back. Do you see any trends toward more personal filmmaking in the postmodern, post-millennium, post-apocalyptical generation?

Well, I don’t believe too much in trends except back in the ’60s. It was so intense that everybody got on similar wavelengths. It was almost like telepathy. There was a real flourishing of film as art. And the strongest people kept on making films. It became institutionalized in the colleges and museums.

I suppose there are people in New York – New York always thinks it’s on top of every trend – who will say what trend is in vogue right now. I don’t know what it is. However, you’re always going to have a few people who do their own thing and punch through and become known. Of course, those are the ones I’m interested in.

We wrote up a young woman out of CCA [California College of Art, Jessica Coccia] who loves your films. Her films were obviously influenced by your work.

Yeah, your work influences people. I was influenced when I started. That’s how you start. Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger, the Russian and French cinema – all were my influences.

The personal film movement influenced a lot. A lot of stuff went into MTV, and also to club films. The clubs just wanted filler up there, and these guys would make long abstract films that were a lot like art films. What do you think is the overall purpose of alternative film? Since Hollywood is the center of commercial film, it would be almost insane to not have an art film center springing up nearby.

Probably. Film is a little enigmatic. Probably the film that has least function – that didn’t try to fill a function of any kind, that just got made at the insistence of the filmmaker – has been the most influential. I’m thinking of these people we’ve been talking about Deren, Anger, Brackhage, Broughton, Nelson, Gehr and some of the earlier ones in New York. You know, I’m not good at names anymore. But what I’m really talking about is that Stan [Brackhage] made films because he believed in a vision. Well, that isn’t really going to do anybody any good, is it?

Except there were all kinds of TV commercial makers who rented Brackhage to learn what’s going on there. Before that, commercials didn’t cut fast. A number of Hollywood directors said they learned to see by looking at Brackhage. Did Brackhage fill a function? We’re talking about what is the function of experimental film. I really don’t know if there is any function. Except what people outside make of it.

I don’t make the films for any functional purpose in society. I’d be making it up if I said I was. I go to work in the studio every morning at 9 and I work until 12. I am either making gallery art or film. I do it because that’s what I do. You can only do what you can do. I can’t make commercial films. I don’t want to. I have no desire to. It’s a rat race.

Have you ever?

Yeah, I’ve dabbled. I was on the Board of Trustees of American Film Institute’s New Producers program – shook hands with famous Hollywood people – from 1972 to 1976.

Right when I was getting to know you.

Me and Ed Emshwiller were the token experimental filmmakers on the board. We thought we were waging a great battle against Hollywood. We’d go to lunch with the heads of studios and TV syndicates and they’d ask us what we did. We’d tell them and we expected some kind of resistance. But they were extremely friendly and interested. They weren’t fighting us – they didn’t even know we existed!

Some of the directors were picking up on us, however. Stan Kubrick researched [experimental film] before ‘2001.’ You know the final sequence? It’s very much like Paul Sharit’s work.

Many people borrowed bits.

I would hate very much to be pegged as someone who influenced Terry Gilliam, or some nonsense like that. I don’t know if he ever saw any of my films. But they were certainly out there long before he started doing that kind of animation.

I think it may be hard to evaluate from your own personal perspective, but in a larger perspective –

I don’t know what the function [of alternative film] is. You have to ask audiences when they see good experimental film and are excited. But there’s a lot of bad stuff out there that has really turned audiences off.

Just like in any medium, there’s really no rhyme or reason. But any art that doesn’t take you on enough of a trip is not worth the journey.

Yeah, it’s very simple, at least to me. I feel that if I make images that genuinely excite my eye, then they will excite the eye of the viewer. Pure art does have a function, in my book. I think that art, from the beginning of civilization, was what kept the spirit of the race alive. I don’t think politicians or religions do it. I think the spirit of Greece, of ancient Greece and Egypt, is in the art we see. That’s where the spirit of those ancient civilizations are. Not the politics or religion, but the people who made the images.

The same thing could be said for San Francisco or Northern California. We’re living quite a civilized life, and we need art specific to our issues.

The Bay Area is full of people who appreciate art. In the ’50s, there were so few organizations and groups of artists doing things. Now it’s very difficult for groups to raise money because there are so many of them. The people who have money to give to the arts are spread so thin now. And the government is not helping much anymore. So you have to figure out other ways to keep making art. It’s not going to pay for itself.

Although gallery art does, I must say. I make money on gallery art and lose money on film. I have forever. But film is where my heart is. I’m very fortunate; I can afford to make the films I want to make [because] they are very, very inexpensive.

What would be a typical budget?

$2500 for a ten-minute film, including five prints. Add on another couple thousand if you want to make a good DVD.

Are you still shooting in 16mm?

Yeah.

Where do you get it processed?

As you know, there aren’t any labs in the Bay Area anymore. But, suddenly I have the lab that we’ve always wanted to have: Fotokem (fotokem.com) They’re in Burbank and employee 800 people. You’d think it would be a rat race or mill, but they’re totally personal. They’re wonderful; they take care of you; and they do it right! They have all the equipment. They do all the 16mm processes, except black and white reversal original, but everything else, they still do.

What are your feelings about 16mm’s longevity?

Well, it’s going down fast. Fewer and fewer of the film festival venues have 16mm equipment, but the big places have great 16mm projection. When I showed at the Lincoln Center Film Festival in New York in the early ’90’s, I walked into the auditorium before the show and there’s this screen 40 feet wide. I said, ‘This isn’t going to work, my image is half an inch wide. They said, ‘Don’t worry.’ The film came on, it was rock solid and the sound was magnificent. I don’t know what they had up in the booth, but it was the right stuff. And at Eastman House [Rochester, NY] and at San Francisco MOMA, the projection is terrific. You know, the big places. They have all these custom-made 16mm projectors that they keep in top running order. But in the smaller venues, it’s getting harder and harder to find 16mm projection.

Won’t it continue as a specialty medium?

I’ve never been very good at prediction. But evidently there are still a lot of people that like to produce in 16mm and 35mm and then take it to digital. But 16mm cameras are becoming a rarity. I don’t know where that will go. But it’s a very good medium, 16mm. You can go so many different ways with it.

Mike Hinton, did you ever run into him at the Art Institute? He had his own company called Interformat, then he moved his equipment to Monaco Labs [9th St SF]. Now he’s back east at the Smithsonian. And this guy David Packard put together a lab to preserve every film gauge there is. Mike did a blow-up of ‘Our Lady of The Sphere,’ paid for by a chain of theaters in England. The blow-up is magnificent. He made it so much better than 16mm. From 16, you can go a lot of different ways. But what you cannot do is go commercial.

A little fuzzy for commercial?

Yeah. You have to be in the 16mm cinema subculture, although it is pretty vast.

I’m still seeing a bit of it. I just saw a show at the Oakland Underground Film Festival [see article] with some 16mm. It looked just like the ’70s at the Art Institute, very personal – and good! It restored my faith in the art film short.

I wish I had known about it. At this point, though, I’m probably more popular in Europe than I am in the United States [a Dutch organization recently produced a film about Jordan, ‘Moments of Illumination,’ by Kathryn Golden, see article]. People who teach film here know who I am. In Europe, jazz is totally alive and so is experimental film. It’s not raging, like it was in the ’60s, when every college in the country was showing experimental film, but it’s in all the big cities. I just did a European tour last September – two shows in Brussels, two in Paris and one in Naples. Did very well.

That’s lovely. Have you seen any young artists coming up that might be able to carry forth the baton?

Yeah, I’ve seen a few. There are young filmmakers, many of them using 16mm.

Hopefully it will continue as a specialty art form. To lose a medium is tragic.

Yes, it is.

—-

Doniphan Blair is a writer, designer, filmmaker, newspaper publisher in Oakland: doniphan@amedianysf.com