Spotlight on Patrick Bokanowski: new work, DCPs, and Blu Rays

Posted January 28th, 2019 in New Acquisitions, New DVDs, News / Events

Patrick Bokanowski is a French filmmaker and animator concerned with the subjective potential of cinema, achieved through distortion of the camera lens and virtuoso optical manipulation. In L’envol and L’indomptable (both 2018), video inputs effloresce into rays of light; both are available as DCPs from Canyon for the first time. The feature films L’ange and Un Rêve Solaire can be purchased on Blu-Ray, and DCPs of the rest of Bokanowski’s work are also in distribution.

L’envol (2018 | 8 minutes | COLOR | SOUND)

SOAR: Choreography of an imaginary journey.

L’indomptable (2018 | 4 minutes | COLOR | SOUND)

THE UNTAMEABLE : Fantastic ride.

Un rêve solaire (2015-2016 | 63 minutes | COLOR | SOUND)

Unlike L’ange, shot in the studio, Un rêve solaire is largely made up of real shots. The actors are no longer played under masks. The actors are us, spectators of unknown representations, or maybe even stellar spectators, a crowd of anonymous spectators standing out on skies of fire and water, but surely a part of a childhood dream during a journey by train.

Battements Solaires (Solar Beats) (2008 | 19 minutes | COLOR | SOUND)

Walking towards the fire. In a ceaseless stream of light, people, landscapes and objects lead us to mysterious regions. Animation film with special effects.

Au Bord du Lac (By the Lake) (1994 | 6 minutes | COLOR | SOUND)

“It is true that the unidentified people being filmed are not there simply for the actions they are performing, but the time that the scene is taking to be completed is also beyond any normal definition. The colors vary, and we are plunged many years back in time, no doubt because the shot is suddenly reminding us of Van Gogh or Gauguin and the color-tones they used. We are not at the side of any identifiable lake, we are swept up in a different sort of space-time context by the light, the movement and the colors that the place evoked in Patrick Bokanowski’s mind. The shore we are on is the quintessence of lakehood, and, as happens in his previous film, THE BEACH, it’s as if the proximity of water metamorphosed everything around, fluidizing all of the matter into endless spirals before our delighted eyes.”

– Jacques Kermabon from BREF magazine, March 1994

La Plage (The Beach) (1992 | 13 minutes | COLOR | SOUND)

“There are now films like THE BEACH which belong to a sort of aristocracy of experimental film – which is just an arbitrary term meaning that a film’s plastic aspect is just as important as its meaning or storyline – and Patrick Bokanowski’s film has an almost classical quality in this sense, insofar as it is composed like a painting, or, perhaps because of Michèle Bokanowski’s contribution, like a piece of music. In THE BEACH, one no longer associates his work with Kafka or Isidore Ducasse, but rather with the light-filled drawings of Victor Hugo or Seurat, Tanguy or even Mir-. It’s as if a period of nightmares had come to an end, and a new sense of something like serenity had taken over.”

– Dominique Noguez from the preface to the Bokanowski retrospective at the Musée du Jeu de Paume, February/March 1994

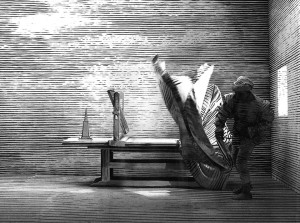

L’ange (The Angel) (1982 | 70 minutes | COLOR | SOUND)

During the seventy minutes of The Angel, viewers see a series of distinct sequences arranged upward along a staircase that seems more mythic than literal. Each of the sequences has its own mood and type of action. Early in the film, a fencer thrusts, over and over, at a doll hanging from the ceiling of a bare room. At first, he is seen in the room at the end of a narrow hallway off the staircase, and later from within the room. He fences, sits in a chair, fences – his movements filmed with a technique that lies somewhere between live action and still photographs. At times, Bokanowski’s imagery is reminiscent of Etienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographs. Further up the stairs, we find ourselves in a room where a maid brings a jug of milk to a man without hands, over and over. Still later, we are in a room where there seems to be a movie projector pointing at us. Then, in a sequence reminiscent of Méliés and early Chaplin, a man frolics in a bathtub, and in a subsequent sequence gets up, dresses in reverse motion, and leaves for work. The film’s most elaborate sequence takes place in a library in which nine identical librarians work busily in choreographed, slightly fast motion. When the librarians leave work, they are seen in extreme long shot, running in what appears to be a two-dimensional space, ultimately toward a naked woman trapped in a box, which they enter with a battering ram. Then, back in the room with the projector, we are presented with an artist and model in a composition that, at first, declares itself two-dimensional until the artist and model move, revealing that this “obviously” flat space is fact three-dimensional. Finally, a visually stunning passage of projected light reflecting off a series of mirrors introduces The Angel’s final sequence, of beings on a huge staircase filmed from below; the beings seem to be ascending toward some higher realm. Bokanowski’s consistently distinctive visuals are accompanied by a soundtrack composed by Michèle Bokanowski, Patrick Bokanowski’s wife and collaborator. Like Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), Bokanowski’s The Angel creates a world that is visually quite distinct from what we consider “reality,” while providing a wide range of implicit references to it and to the history of representing those levels of reality that lie beneath and beyond the conventional surfaces of things.

Dejeuner du Matin (1974 | 12 minutes | COLOR | SOUND)

This very short film takes us outside of time as we know it and drops us into a different kind of timespan and into a different world. To a certain extent it can be called ‘surreal,’ but only in reference to the filmmaker’s own vision. It can be called a dreamscape, but don’t go looking for any hidden meanings in these disturbing images. Such as that long nocturnal hallway we’ve walked down in our dreams, down which psychoanalysts have followed their customers, or on their own behalf. It leads us into the deepest depth of ourselves.

“Plastically speaking, the work is superb. It touches us physically before affecting us metaphysically. In the dark depths of a field, a strange and displaced peasantry is scything an invisible yield.” – Claude Mauriac from V.S.D. magazine, June 1979

La Femme qui se Poudre (A Woman Powdering Herself) (1972 | 18 minutes | B&W | SOUND)

“Yet it’s very much like a new masterpiece that blazes its own trail without resembling anything else that has been seen before (although you could claim a vague family resemblance with Goya or German expressionism). But whatever one wants to analyze or not analyze in this film, it is a work which disturbs one deeply. The music (by Michele Bokanowski) is pitched high, as if synthesized from the whistling wind; it’s the sound a flying saucer might make along with Tibetan trumpets and overheard bits and pieces of people talking in a language you don’t understand. You wonder how everything you are looking at was fabricated. There are a few double exposures, or else ‘real people’ wearing grotesque Frankenstein-like masks or stockings over their faces. They are either filmed through a dirty glass or else they metamorphose into drawings (a character can be drawn or else volumes come into focus and assemble themselves into a weird and yet coherent form): as a result, the space the film is describing is being constantly scrambled; it’s a film without any floor in it and, as a spectator, when you are watching it, even if you are comfortably seated, your own seat leaves the ground. One notices these briefly passing creatures (one of which is, yes, a woman powdering herself) slowly and deliberately undertaking acts you don’t quite understand, but which are clearly of a ghastly nature (perhaps a murder?); one watches two ‘real’ characters suddenly change into ink spots while a bombardment of drawn or painted meteorites explodes on what might be the ‘earth’; one looks at somebody pouring coffee into a full cup which then overflows into an endlessly dark and ink-like trail; at which point you say to yourself that what is going on here, in this black and upsetting film, has the logic of a nightmare.”

– Dominique Noguez