What the Water Said, Nos. 4-6

- David Gatten |

- 2006-2007 |

- 17 minutes |

- COLOR |

- SOUND

Rental Format(s): 16mm film / Digital File

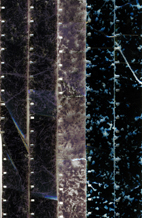

In this final installment of a nine-year project documenting the underwater world off the coast of South Carolina, once again both the sounds and images are the result of the oceanic inscriptions written directly into the emulsion of the film as it was buffeted by the salt water, sand and rocks; as it was chewed by the crabs and fish. Named one of the "50 Best Films of the 21st Century" in Film Comment's International Critics Poll.

"What the water said is literally inscribed on the strips of unexposed celluloid that Gatten cast into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South Carolina. Encased in crab traps, the fragmented filmstrips harbor mystical messages from the underwater world, a source of seemingly never-ending fascination. The sea, its salt, sand and rocks, and its gnawing creatures have created the film's inimitable textured patterns and sounds, while passages from Western literature's greatest sea odysseys - from Robinson Crusoe to Moby Dick - remind us of the sea's singular place in our imagination." - Andréa Picard, 2007 Toronto International Film Festival

"Gatten's WATER project has been brilliant from the start, and as more and more filmmakers turn to digital media it only seems more so. Take unexposed film stock, submerge it in crab traps off the coast of South Carolina and, as the water batters and pockmarks the film with more or less turbulence, greater or lesser concentration of rocks, sand, and other emulsion-scratching items, the film will provide a hard material record - a chemical-to-chemical transcription - of an aspect of the natural world. Parts 1-3 were characterized by lovely color-fields and yarn-like scratches, often building in density but usually, if memory serves, returning to a placid state, at least on the movie screen.

But nothing prepared me for the full-body jolt, or the conceptual exactitude, of 4-6. Gatten breaks up the passages of film with date titles, providing a diary-cum-filing system throughout the course of the film. This helps to orient us as we marvel at the palpable difference a mere 24 hours can make in the life of even a relatively small pocket of ecosystem.

Number 4 documents early January 2006, and the images begin as wiry white lines amidst a base of rust-colored emulsion. Over the course of three days, the white bulks up, at first becoming an aggressive skein against the rust (rather like a late Brice Marden canvas), then eventually becoming pulsating blotches, resulting in two flat fields grinding against one another in the picture plane, vaguely Adolph Gottlieb or Clyfford Still but not exactly either.

Number 5, in September, provides a black field, with thick, jagged white lines carved out of it, first one or two and eventually a torrent. This section recalls Brakhage's work but, due to the relative randomness Gatten's procedure insures, Number 5's lines and forms never describe space in the careful, even classical ways that Brakhage did. Instead, the screen is a lighted field of perpetually shifting spatial relationships, a dark void traversed by crackling energies, as though we've entered the atom.

Number 6, in the final days of 2006, begins as Number 5 did, but instead of lines, we have rounded chunks of white, as though large pebbles knocked the emulsion out bit by bit. These rounded areas increase in number, and soon you notice something startling. Each of these spaces has a red and blue penumbra, alluding to 3D film imagery and even beginning to round the forms out into spheres but always remaining securely on the surface. These multicolored forms eventually take over the screen in a gorgeous cataclysm. Water, it should be noted, is a sound film, and the soundtrack, like the image, is comprised of the physical remnants and residue on the film's sound strip. So we get a thumping buzz that acts not as accompaniment to the images but as indexical correspondence. (There is even the brief lag between sound and image due to the disparity between the two tracks on every filmstrip.) And so, by the time of Number 6's conclusion, the ocean is giving us metaphors we know aren't fair. The screen is bursting with popcorn! The bursting colors and aural pops bring us to the end of our fireworks display! But of course, these aren't "pictures."

And this brings me to Gatten's final intervention. At the start of the film, between each section and at the end, Gatten inserts a substantial text from the Western canon which addressed the awesome power of the sea - an excerpt from Moby Dick, Fernando Pessoa's "Maritime Ode," a near-drowning scene from Robinson Crusoe, and a description of the blackest of seas from Edgar Allen Poe's "Descent into the Maelstrom." To me, at least, the point is clear. However beautiful and exquisitely wrought these passages may be, they will always fail to capture the elemental character of the ocean. What the water "says" is never verbal, and bears only the slightest relationship to human life. Gatten's films transcribe this non-subjective, impossible-to-psychologize voice, and even if these films will also prove incapable of harnessing these natural events, they will bring us quite a bit closer. Nearly 150 years ago, humans began inventing photography, and they marveled as they took pictures of themselves and their own historical doings. Now, humans are abandoning photochemistry by and large. But perhaps the earth might reclaim it in order to give us a more accurate picture of itself." - Michael Sicinski, Cinemascope